Bargainsville, Arizona

The phrase “too much of a good thing” applies to cities, too—even when that ‘good thing’ is a reputation for bargains. Such was the case in Tucson, AZ, in the early 1980s, when not a single day passed without a barn-buster sale. Don Schellie, beloved former columnist for the Tucson Citizen, wrote an article detailing the Old Pueblo’s predilection for bargain mania in April 1981. “Mostly these days it’s the Spring Sales,” Schellie begins. “Next week though, it’ll be something different—sure as shootin’ there’ll be a sale of another sort—because Tucson’s a Sale Crazy City.”1 He then provides a laundry list of sales in six categories—Shop Now, Happy Sales, Sad Sales, Sale Away, Calendar Sales, and Nice Price Sales. Some of the more unique entries include the Clean Sweep Sale, Expannnnsion Sale, Flood Damage Sale, Owl Sale, Groundhog Day Sale, Carnival Sale, Carload Sale, Sidewalk Sale, and Clean Up, Paint Up, Fix-up Sale.

Schellie enjoyed a bargain as much as the next guy, but the preponderance of sales listed in the article suggests that things had gotten out of hand. “Most any occasion’s an excuse for a sale in Tucson,” Schellie explains. “Mention Geo. Washington, for openers, or the end of a month, first month of the year, Halloween, your Granny’s birthday—you name it—and visions of dollar signs dance in the merchant’s wee little heads.”2 And with the deluge of never-ending sales, finding ways for your business to stand out from competitors was critical. In the article, Schellie reveals one of the chief tactics many retailers used at the time to get an edge: “Follow the searchlights that play in the nighttime skies,”3 Schellie tells bargain hunters looking for a sale.

The Luminous Metronome

Searchlight advertising was very popular in the 1970s and 1980s. This advertising method involved placing powerful searchlights on the store premises and beaming their lights into the night sky to attract attention. Like a luminous metronome, these searchlights moved across the sky in a regular sweeping pattern, sometimes criss-crossing with columns of light from nearby searchlight units. Back then, it was common to see searchlights in the night sky. I remember my Dad driving the family to Nana’s house on the east side of town in his Chevy truck. 22nd Street had several car dealerships, many of which used searchlights as a gimmick to lure traffic to their site. Looking out the windows of the camper shell in Dad’s truck, I remember seeing these moving searchlights projecting their wide white beams all the way to the heavens.

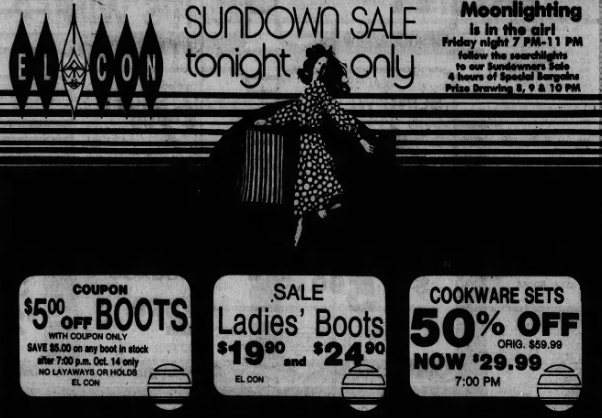

El Con Mall in Tucson, AZ, was one of many Tucson retail stores that utilized searchlight advertising. On Friday, October 14, 1977, for example, the mall hosted a huge “Sundown Sale” from 7 to 11 p.m. “Moonlighting is in the air,” the ad proclaimed. “Follow the searchlights to our Sundowners Sale.” In addition to discounted prices on many items, there were prize drawings at 8, 9, and 10 p.m. Using searchlights for a sundown-themed sale was one of many marketing tactics that El Con Management used to lure people to the mall over the years.

Unintended Consequences

With so many sales, it’s easy to understand why Tucson businesses turned to gimmicks like searchlight advertising to get a competitive edge. Over time, searchlights became a heated issue. Tucson is a world-renowned hotspot for astronomy. As the self-named “Astronomy Capital of the World,” Tucson prides itself on the number and density of professional-grade telescopes within a 60-minute drive of the city’s downtown. For these telescopes to work effectively, dark skies are required. In the 1970s and 1980s, advertising searchlights contributed to “sky glow” that prevented telescopes on Kitt Peak and Mt. Hopkins from seeing objects deep in space. Light from the sweeping beacons illuminated particles in the atmosphere, creating a haze that extended beyond the reach of the searchlight. This caused big problems for the local observatories.

In addition to the difficulties they posed for astronomers, advertising searchlights were unsightly. Imagine going outside after dinner to enjoy the evening and view of the night sky, only to see it awash in a pale white haze caused by searchlights. At times, the Tucson night sky resembled London’s during the Blitz, criss-crossed by sweeping searchlights. One Tucsonan, Nancy Laney, wrote a letter to the editor in August 1975 voicing her outrage. “The beautiful summer evenings in Tucson are certainly one of the very nicest things about living here,” said Laney. “But night after night, the sky is marred by the glaring, intruding sweeps of a searchlight across the sky, obscuring the already limited number of stars visible from within the city.”4

The Modern Digital Glow

Now, a quarter-century into the new Millennium, it’s safe to say that too much digital technology has not been a good thing for most people. The advent of smartphones, in particular, has brought changes that humanity is struggling to adjust to. The Internet and laptop computers went mainstream for most families in the mid-1990s. Then came the iPod and MP3 players in the early 2000s, along with the first front and back-facing camera phones. The first modern smartphone was introduced in 2007 with the Apple iPhone. It combined the functionality of a phone, video recording device, camera, and computer. The following year, the first Android phone was released. Smartphones have revolutionized the way we communicate. Like the advertising searchlights, they have also led to some unintended consequences.

Like the white searchlight beams, the glow of a smartphone screen never fails to capture our attention. The light draws us in like moths to the flame. Wherever we are and whatever we’re doing, we can’t resist the urge to pull out our smartphones to check messages, read the news, watch videos, etc. Second, like the sweeping searchlight, a smartphone places our minds in a perpetual state of scanning, even if the phone is out of sight in our pocket or purse. Whatever we’re doing, some part of our mind remains on alert for incoming calls or that “ding” that indicates a new text message has arrived. Third, just as searchlights contributed to the skyglow effect that prevented people from seeing the stars, smartphones have contributed to a collective withdrawal from embodied experience that characterizes so much of the way we now spend our time. Today, even cherished family events like a Thanksgiving Dinner resemble that London Blitz scene described earlier, with the glow of smartphones replacing the advertising searchlights of previous decades.

A Practical Solution

What’s the solution? For that, we return to Nancy Laney’s letter to the editor. After voicing her complaint, Laney offers her practical solution to the problem of the advertising searchlights. “If the gas stations, stores, restaurants, etc. using these searchlights are interested in making their presence known, there must be more effective and less offensive ways of doing so,” Laney surmised. “The use of searchlights for advertisement is surely a waste of energy and a needless form of ‘sight’ pollution.”5 Turns out, Laney’s assessment was more than practical; it was prophetic. Laws banning the use of advertising searchlights were eventually passed, preserving Tucson’s dark skies and allowing astronomers and others to enjoy their stargazing.

While I don’t propose passing laws to ban smartphone usage, every person should take a serious look at how much time they spend on their phones. The glow of our smartphone screens keeps us trapped in a state of disembodied experience. While we are caught in that glow, we can’t see beyond the parade of trivialities that keep us stuck in the shallows of life. If you want to move past the surface issues to experience life’s deeper mysteries, put away the smartphone and spend more time in the here and now. To witness the awe-inspiring beauty of the stars, you must remove the glare that shields your eyes from the heavens.

FOOTNOTES

1Schellie, D. (1981, March 26). Anyone feel like going for a sale? Tucson Citizen, p. 2.

2Schellie, D. (1981, March 26). Anyone feel like going for a sale? Tucson Citizen, p. 2.

3Schellie, D. (1981, March 26). Anyone feel like going for a sale? Tucson Citizen, p. 2.

4Laney, N. K. (1975, August 12). A waste of energy [letter to the editor]. Tucson Citizen, p. 22.

5Laney, N. K. (1975, August 12). A waste of energy [letter to the editor]. Tucson Citizen, p. 22.